Living our own experience is hard. Most of us live an interpretation of it. One that we, ourselves are projecting through our thoughts. We direct almost all of our attention to this projection without realising we are doing it. It has its own array of filters that alter our perception, based on what we have experienced in the past and our own and others’ interpretations of it. While in some ways helping to keep us alive, if left unchecked, this can also present a challenge to experiencing our lives as they are.

In addition the projections we gather and carry about others’ experiences and their interpretations, sit, almost invisibly alongside our own. We haven’t had the associated experience but we adopt the projection. In this way we can expand our imagined understanding of our world beyond ourselves. Which can be helpful if held with awareness of limitations. The projected images flashing across our consciousness can be very compelling and often pass for reality itself. The theoretical being accepted as the actual. The imagined as real. Yet we consciously, or more often unconsciously, compare our projections with those that have colonised us. Adding yet more challenge to living our own experiences in any given moment. Until we lose track of what is ours and what we have adopted.

We used to construct these comparisons by observing those in our environment. People in similar situations and living similar lives to us. Within the reach of our senses and knowable that way. There was fair context. Someone with more sheep, a sharper sword, a more colourful dress, faster car, a pulpit, badge, title, more money or power. Or the same or less or just different. We used our language and told stories to capture our projections for others to hear. These stories were then portable allowing comparisons to come from outside of our immediate environment. We sang them. We made idols. We created art. We wrote them down. In this way we learned about what was beyond our own worlds, providing inspiration, practical ideas about how we might live, sharing knowledge and enriching our imaginations. We also invented ways to compare our lives with others living vastly differently to us. Inviting aspiration to reach for the moon without knowing what was required to get there and dissatisfaction with our lives without knowing the truth of those living the stories. This continued for many generations as we found new and faster ways for stories to travel further and wider.

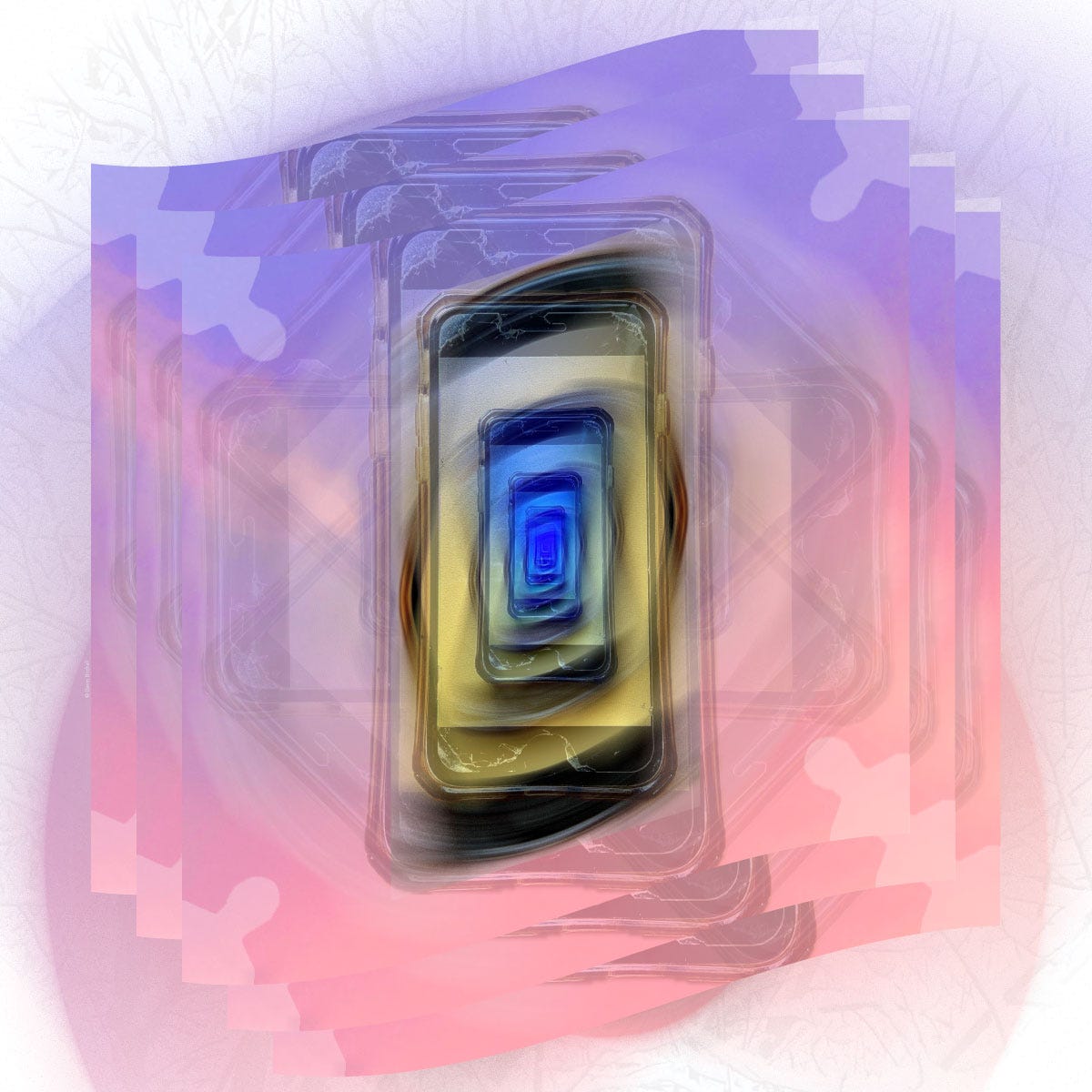

Eventually, and crucially, mirroring the images flashing across our consciousness more vividly than ever before, we rendered our stories on screens, with movement, colour and sound. Such convincing displays that our minds struggle and often fail to recognise them as literal two dimensional recreations. We exported and replicated our partial, imaginative, interpretations. One of our most amazing strengths and disturbing weaknesses. Using motion and hue and noise but lacking depth and touch, and scent and taste and heft and context and meaning. We no longer needed to imagine different realities. Others had done this for us. To the extreme. Guiding us to feel in particular ways rather than what we might feel ourselves if we were present. In all of their enhanced, amplified, saturated, carefully crafted ways they sit alongside our own inner experiential projections. Which may seem insipid and unexciting, shrinking to our attention when matched to these unrealities, yet leaving out the unwelcome sensations that would come with direct experience.

A rare visit to the cinema required us to leave our homes, travel and pay before giving ourselves to other stories. ‘Cinema’ is from the Greek and roughly means ‘a record of movement’. We externalised our inner projections and shared them at a grand scale. They were larger than us, louder than us, elsewhere and clearly belonged to someone else. Demonstrably separate from us and this was celebrated. Most of us received while a small few gave. Then we found a way to bring the screens into our homes and a television sat in our living rooms. ‘Tele’ being of Greek origin as well and meaning ‘far off’. Spaces which used to be for living our own lives became spaces for living in our imaginations, the stories of others. Others who were far off from us, our worlds, our lives. Permanent and unlimited access to stories, not our own, took our attention further away from our personal, intimate, unique experience. The obvious separateness of the cinema screen was lessened as the television screen belonged to us, sat with us in our homes, seemed to be be unassociated with any kind of payment or exchange from us and appeared to be under our control.

But we could still move away from a television. We had to eat, to work and to sleep. Then they became essential and more than one seemed necessary. We moved them into our bedrooms and sleep was no longer distinct. Even in kitchens and showers and aeroplanes and shops and they became bigger to better draw and hold our attention. They multiplied and became ubiquitous. The number of channels increased, specialist channels lessened context even more and the opportunities to learn new stories and interpretations for comparison with our own ballooned further. Most of us still received but a greater number gave. The locus of viewers attention was moved more distant from their own experience, and even their interpretation of it, and even comparisons from their environment based on their full spectrum, visceral, sensory experience. It became divorced from their sensory reality, dispersed across the world and its cultures and diminished in its richness and anything like fair context. At least there was a hint about what was happening in the name of this kind of screen. It wasn’t so obscured if you knew your Greek.

You are reading this on a different kind of screen. Maybe a ‘desktop’. Named based on where you might find it and that being because it is too big to carry easily. Or a ‘laptop’. Again, named based on where it might be found or where the creators imagined you using it. A place usually reserved for a pet, child or lover and signalling that this kind of screen can be taken with us, away from the desk into our intimate spaces. Not so ‘far off’ anymore. But not everywhere. Or perhaps, most likely maybe, you are reading on a truly portable little screen that fits the hand and pocket. Not on ’top’ of anything and not named in a similar way perhaps due to it retaining the nomenclature of the spoken communication lineage, phones, that it was combined with, rather than its visual communication lineage, screens. Maybe because it is so ubiquitous it is not ‘on top’ of’, or separate from, but within our lives. Taken, literally, everywhere.

Our own experiences now exist not only alongside our interpretations and projections based on past sensory experiences and those of others we live near, but on a constant, never ending, stream of stories communicating the interpretations and projections of others who are mostly very far off. But they do not seem far off. Being in our palms and our pockets. About our person permanently. Most significantly in our minds and often, sadly, by association our hearts and bodies. The distinction between device and mind has become almost invisible. Almost non-existent. The viewers locus of attention has become so close that it is possible to imagine these devices and what they present being part of us, when they are not. Which makes it incredibly hard to notice what is happening and causing people to respond very strongly if challenged. Our relationships with our individual devices have become such a personal experience and part of identity that open and continuous access seems to have become adopted as an irrefutable natural law.

The stories of ‘other’ are now received by everyone and anyone and given by everyone and anyone. Irrelevant of their intention, skill, location and any other characteristic they might or might not exhibit. The illusion of fair context remains but the assistance of it for sense making has gone. A failsafe, that what we experienced by screen was created by a group, with the inherent coordination, checks and balances that involves, has fallen. Any individual, anywhere can share anything and we can be with it if we choose to. Indefinitely.

Which is amazing and wonderful and freeing. My wondering here is not anti-anything other than unconscious living. How much choice we exert is the most important point. It can seem like we have no choice. Huge energies are exerted to influence how we interact with our individual devices and minimise our ability to do so with full agency. The devices do everything and increasingly more. In their presence our experiential comparison set has expanded to practically infinite through the stories of others. Yet our ability to discern whether those stories are suitable for us to include in our understanding of our own worlds does not appear to have adapted as yet, or as much. The vast majority have accepted these changes, literally, with open arms and palms. Closer and closer the screens have come. They are so convenient. So accessible. So beguiling. So essential. We can’t live without them. But perhaps it is not so easy to really live with them.

Our own, direct experience, of where we are and what we do and how our relationships are and what the land and other life around us are up to and what the weather brings and our own bodies and our stance to all of this stands little chance of thriving, if even surviving, by comparison. No single person or group has done this to us. It is not planned. Many seemingly sensible decisions, one after another, to make our lives better, have led to this. How we respond as individuals will influence how everything continues. We can only act in our lives. To do that we need to be in them. To live our own experiences. Not the partial experiences of others, communicated through the immense constraints of two dimensional, filtered, partial, curated, unwhole experiences and take that to be our lives. We need to choose what we allow to influence and even replace our experiences, in what ways, for how long and for the sake of what.

Perhaps these latest ways we have of sharing our stories and experiences with each other do have a ‘place’ to which they belong. To which we have, unconsciously, unintentionally, drip by drip, allowed them to belong. Not ‘desk’ or ‘lap’ but life. Maybe we have unknowingly given them the position of being on top of our lives. Screens that are ‘Lifetop’. Gently, imperceptibly, gradually, pushing our own experiences of life down into unconsciousness, if we use them in the way that they have been designed for us to use them. It is very hard to make choices that oppose such powerful forces. But experiencing the life that we each have, individually and together, fully and truly, we might find motivation enough, if we can see that our lives literally depend on it.

Judging our lives by external measures can leave us feeling lacking. Integral development coaching helps to find relevance and appreciate our lives as they are.